The imagery that conforms the coat of arms emblazoned on the central white band of the Mexican flag is quite complex and unique; it is also called “El escudo nacional” (“The national shield”) and it acts as a seal on official government documents, such as passports, and on the back of all Mexican coins, as shown in the photo. The theme of an eagle standing on a paddle cactus plant comes from the fascinating legend of the foundation of Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Mexica civilization (popularly known as the Aztec Empire*.) The legend tells of an origin place called Aztlan (most likely somewhere in the Northwestern regions of Mexico) where tribes sharing the Nahuatl language lived; they were all Aztecah – people from Aztlan. Even though their language and demonym were uniform, each tribe had its own idiosyncrasy, and even different gods. Sometime in the 13th Century, several groups left Aztlan; one group were called the Mexica (either from Nahuatl metztli – moon or metl – maguey; and xictli – navel, or centre), and they were followers of the god Huitzilopochtli. According to the legend, they were to wander and remain derelict until they found an island, and saw the sign given by this god, which described an eagle on a paddle cactus.

The imagery that conforms the coat of arms emblazoned on the central white band of the Mexican flag is quite complex and unique; it is also called “El escudo nacional” (“The national shield”) and it acts as a seal on official government documents, such as passports, and on the back of all Mexican coins, as shown in the photo. The theme of an eagle standing on a paddle cactus plant comes from the fascinating legend of the foundation of Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Mexica civilization (popularly known as the Aztec Empire*.) The legend tells of an origin place called Aztlan (most likely somewhere in the Northwestern regions of Mexico) where tribes sharing the Nahuatl language lived; they were all Aztecah – people from Aztlan. Even though their language and demonym were uniform, each tribe had its own idiosyncrasy, and even different gods. Sometime in the 13th Century, several groups left Aztlan; one group were called the Mexica (either from Nahuatl metztli – moon or metl – maguey; and xictli – navel, or centre), and they were followers of the god Huitzilopochtli. According to the legend, they were to wander and remain derelict until they found an island, and saw the sign given by this god, which described an eagle on a paddle cactus.

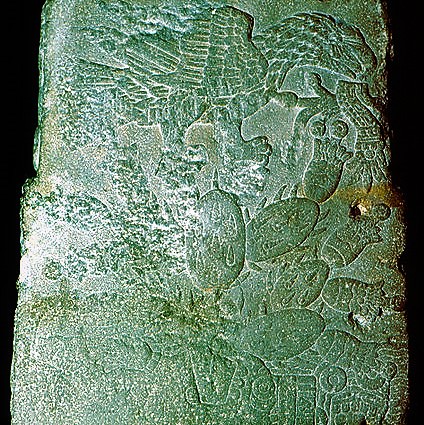

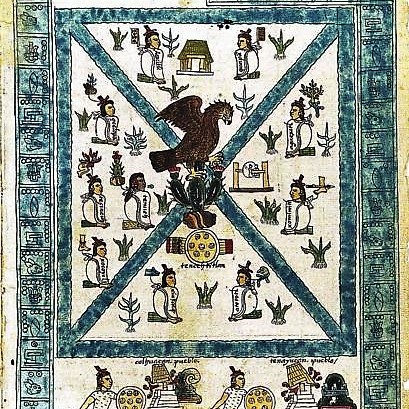

This origin legend is depicted at the back of the pre-Hispanic sculpture “Teocalli of the Sacred War” (see photo below, left); the eagle is believed to be a representation of Huitzilopochtli, victoriously holding in its beak the glyph atl-tlachinolli – burning water (represents the sacred war); the cactus appears to grow from a representation of a defeated Chalchiuhtlicue, goddess of lakes and streams. The Mexicas saw the sign on an island in the Texcoco lake; they named their city Tenochtitlan, founded in 1325 AD, which eventually became the largest urban area in Mesoamerica. After the fall of the city in 1521, the Spanish conquerors called the natives mexicas or mexicanos, and founded Mexico City over the ruins of Tenochtitlan. Several codices from the XVI century and later on, depict the imagery of the legend as well, but replacing natural themes for the glyphs, considering pre-Hispanic religious items at fault. They show water (or the glyph for atl – water) instead of the goddess, and the eagle’s beak is empty (such as in the Codex Mendoza, folio 2r, shown in the photo below, centre), or holds an animal instead of the “sacred war” glyph, as in the Tovar codex, in which the eagle is holding a bird (photo below, right):

The Codex Tezcatlipoca depicts an eagle attacking a snake; it is one of the few original native codices that survived the massive destruction of pre-Hispanic documents by the Spaniards. It is argued that the most accepted version during colonial times had a serpent, as it fit the Catholic symbolism of a battle between good (represented by the eagle) and evil (snake).

The current Coat of arms (at the top of this post) shows an eagle holding a rattlesnake (one of the most common species in Mexico), with the addition of European symbols of victory and peace, in the oak and laurel leaves encircling the half bottom of the image, tied with a ribbon with the national colours, adopted when Mexico became an independent nation.

As I have mentioned in previous posts, the paddle cactus (nopal) and its fruit, the prickly pear (tuna), have been part of the Mexican diet since pre-Hispanic times; I have shared two recipes featuring nopales: Sautéed Paddle Cactus (Nopalitos), photo below, left, and Grilled Paddle Cactus with Melted Cheese (Nopales asados con queso fundido), photo below, right (click on the titles for printable recipes):

This post is getting too long, so I will leave another recipe with paddle cacti for my next post: “Mexican Sausage in Green Sauce with Paddle Cacti” (Longaniza en salsa verde con nopales), which includes pre-Hispanic ingredients, combined with European elements, just like “El escudo nacional.”

*NOTE: Alexander von Humboldt was part of an expedition to the Americas at the turn of the 19th century, including Mexican territory in 1803 and 1804. About ten years later, he published Vues des cordillères et monuments des peuples indigènes de l’Amerique (translated to English in 1814 as “Researches concerning the institutions & monuments of the ancient inhabitants of America: with descriptions & views of some of the most striking scenes in the Cordilleras!) In this publication, von Humboldt erroneously refers to the Mexica as aztèque, which appeared as “Aztec” in the English translation. Although during the colony the Spaniards always used the terms mexica (pre-Hispanic) and mexicanos (Spanish word for natives of Mexico), the term “Aztec” stuck amongst many historians and scholars to refer to the pre-Hispanic civilization and its people, as a way to clearly differentiate them from colonial or modern Mexicans. Hence, Tenochtitlan is generally described as the capital of the “Aztec Empire” (even in Spanish, the term “Imperio Azteca” is accepted), and “Mexico” names both the city built on its ruins and current capital, and the modern independent country.

Coat of Arms, Teocalli of Sacred War and two codex pictures, all from Wiki Commons (Public Domain.)

I live in a mountainous region surrounding Lake Chapala, about an hour from Guadalajara. On a mountainside between the town of Ajijic and my village, San Juan Cosala, there is a largmountain that is covered in scrub, but a huge portion in the middle of all the scrub never becomes covered by vegetation.This large stony area is in the shape of an eagle with its wings outspread, its beak facing to the side. Just one small green shrub grows in this area in the exact location of the eye. It is a local legend that as they wandered, the Aztecs first saw this as the sign they were looking for and settled in San Juan Cosala for many years, conquering or driving out the local tribes. Many in the village, including the fine artist I am lucky enough to have illustrating my books, bear Aztec names. After many years, they moved on to found what eventually became Mexico City.

LikeLike

Wow, I didn’t know of that legend, thanks for sharing, Judy!

LikeLike

Wonderful!!!! I think there is a tiny typo. Were the people to wonder or to wander? But the article is so important for the book. You are really an excellent story-teller. You make everything so interesting. xxxxxxxxxAnya

LikeLike

Ah yes, thank you, I’ll get to that. Thank you Anya! xxxx

LikeLike

Interesting to learn about the naming of the cultures. It’s a bit like how the native people came to be called Indians.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love your blog! I learn so many fascinating things. I saw nopales at the international market the other day and here is your post with delicious recipes convincing me to try them! Thanks for all you share so generously.

LikeLike

I hope you do try them; thank you for your kind comments, Victoria!

LikeLike

I like the clarification about the Mexica and Aztec names. I just learned about it this week in my readings by Matthew Restall. : ) Rebecca

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating, thank you very much!

LikeLiked by 1 person