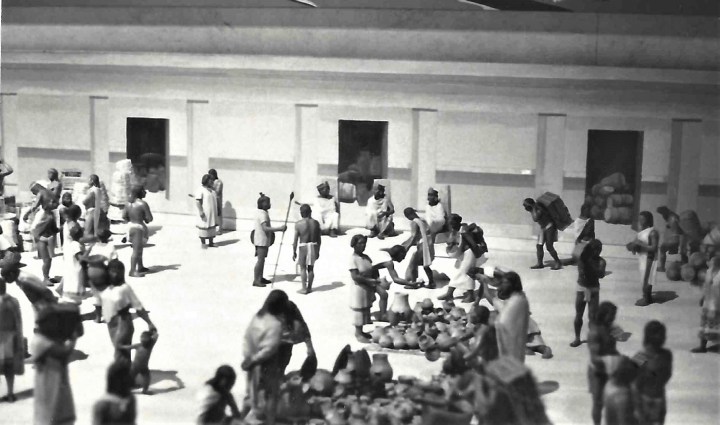

There is no doubt that markets have always been a central part of Mexican society. Tenochtitlan (modern day Mexico City) was founded in c. 1325, and after the Mexica (Aztec) grew into an empire, and the city became its capital, trading and commerce flourished, both as a tributary system (penalties paid in goods from conquered territories) and as an open market (arguably modelled as a complex supply and demand system). Each calpulli (district, from Nahuatl calpōlli – large house) had its own local tianquiztli (marketplace), but the pochteca were traders who operated in long-distance markets to provide items from all around Mesoamerica (Mexico and Central America), and there was also a central marketplace in the sister city of Tlatelolco (at the top of this post, a detail of the Tlatelolco Market diorama at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico city, photographed by my father, c. 1970).

By the time Spanish conquerors arrived to Tenochtitlan in 1519, the city had a population close to 400,000, the largest urban concentration in all of native Mesoamerica. Hernán Cortés and his men were marvelled by the size and degree of development both in Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco, where the central market operated around the clock, occupying a vast space, as described by Cortés on his second letter to king Carlos V as being ” … twice as large as that of the city of Salamanca [in Spain], surrounded by porticoes, where are daily assembled more than sixty thousand souls, engaged in buying, and selling; and where are found all kinds of merchandise that the world affords.” (quote from a translation by the American Historical Society.) Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who was part of Cortés’s company, describes the experience of visiting the Tlatelolco market in one of the most famous passages of his book “Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España” (True History of the Conquest of the New Spain, 1568); a translated excerpt notes that “… When we arrived at the great plaza they call Tlatelolco, the like of which we had never seen, we were amazed at the number of people and the amounts of merchandise to be found there, and at the good order and control that everything had.” Wild animal skins, gold, silver, and precious stones were traded, and there was also human traffic; special cotton clothing, pieces of copper of standard size, and cacao beans were used as currency. There were materials and supplies for every trade, such as wood, brick, timber, paints, tools, birds (fowl and prey), medicinal herbs and roots, etc. Of course food stuffs and cooking utensils occupied a good part of the market square.

Although nowadays supermarkets and chain stores have taken over a good part of the shopping scene, outdoors mercados sobre ruedas (farmer’s markets “on wheels”) and tianguis (derived from the original word tianquiztli) are still ubiquitous on streets and squares all around the country. There are also well established neighbourhood markets, and, in true Tlatelolco market fashion, behemoth supply markets, such as La Central de Abasto, the largest whole sale centre in Mexico, and La Nueva Viga, the World’s second largest seafood market (from “Food, Health, and Culture in Latino Los Angeles”, by Sarah Portnoy; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016; pp 85-86). A great variety of products may still be found in very close forms as they would have looked at a pre-Hispanic tianquiztli, for example, common beans and summer squash:

Beans and squash, along with corn, formed the “three sisters” powerhouse of complementary crops in the region’s fields (milpa), and a balanced meal at the table:

Tomatillos (such as miltomate, photo below, left) would be purchased for a good salsa, along with some hot peppers (chiles) to add a nice kick (dry red chiles, photo below, right):

Fruits like avocados, pitaya, prickly pear and, as shown below, mamey (Pouteria_sapota) are all originally from Mexico:

Just as described by Cortés of the Tlatelolco market, modern Mexican markets offer “earthenware of a large size and excellent quality; large and small jars, jugs, pots, bricks, and an endless variety of vessels, all made of fine clay, and all or most of them glazed and painted”:

After the Spanish conquest was completed, a long period of adjustment and exchange began at all levels. Religious, political, and linguistic fusions took place, reflected also at the marketplace: rice and wheat joined, and for a while even displaced, corn; sugar cane was well accepted amongst the existing sweeteners, such as honey, and agave and corn syrup. In the photo below, at an organic market in Mexico City, produce such as mango, apples, watermelon, and tamarind have become so naturalized as to appear native, amongst piles of tomatoes, and sacs of cacao beans and amaranth:

All sorts of birds, from doves to turkeys and wild fowl, as well as their eggs, were sold in Tlatelolco; insects, turtles, rabbits, and dogs were all common purchases for consumption. Spaniards brought chickens, cattle, sheep, goats and pigs, which now are the main offerings of Mexican butchers (photo below, left). A typical scene at a neighbourhood market, on the right, shows the upbeat atmosphere and genial disposition of the vendors, in modern Mexico:

Many prepared food was also sold at pre-Hispanic markets, notably, tlaxcalli (corn tortillas) and other corn preparations, such as Tlahtlaōyoh (tlacoyos, elongated corn patties with fillings), which were mentioned by Cortés as tasty and conveniently portable concoctions; they were probably cooked on grills placed over portable clay braziers similar to those shown above. In the photos below, corn tortillas freshly cooked over a comal (Mexican flat grill), on the left, and a wide selection of prepared foods, with a fusion of Old and New World ingredients, on the right:

In my next post, a pre- and post-Hispanic view of the tlacoyo, the mother of all corn-dough street foods.

That was fascinating. We don’t reall have a market tradition. I guess there was one once, but it must have died out. But, I have seen it when I have visited other countries. Markets here tend to be a bit ubiquitous, although there is a growing tendency to use them to promote local, artisan food.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the description of the historical markets. Very interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you liked it, thank you, Rebecca!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Mexican markets are like a wonderland, Irene. Thanks for sharing your photos.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not much of a shopper – at least the way we do it in the U.S. But I could wander all day through the open air markets with produce, meats, flowers, textiles, and local crafts. I’ve seen them in Europe and a few in the states, but uncommonly. I like that Mexico and other Latin American countries have preserved this method of commerce. It’s so vivid and absorbing. Thanks for sharing all these wonderful images and the history behind them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here in the US the only true urban markets I recall were in Baltimore, Philadelphia and Boston. Boston’s Hay Market used to be a joy to visit; especially near closing time. Back before they relocated it New York’s Fulton Fish Market was a unique experience. I haven’t thought about these for a while. Lots of folks develop multigenerational contacts with particular vendor carts and stores. It’s a lot different than a super market!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great info, thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great post!

LikeLike

Thank you, chef Mimi!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love mercados, one of the first things I do when I go to Mexico is visit a mercado. Very interesting history you present here.

LikeLike

Yeah, mercados are fun; thank you for your kind comment!

LikeLiked by 1 person