Click here to go to printable recipe: Puff Pastry Reverse Method

Click here to go to printable recipe: Orejas & Abanicos

In my previous post, I talked about Mexican sweet bread (pan dulce), and that has set the tone to share this recipe for the sweet treats pictured at the top of this post, and for comparison, some store-bought ones shown below:

In Mexico, they are called orejas, which translates literally as “ears” from Spanish; the name comes from the shape somewhat resembling a human ear. As many sweet breads, orejas came from Europe, where they are called, also inspired by their shape, “palms” in France (palmier) and Spain (palmeras), “pig’s ears” in Germany (Schweineohren), and “sweet hearts” in the UK, to name a few. The treats on the right side at the top of this post are a slight variation, called abanicos – fans. Some sweet bread recipes have changed to adapt to local ingredients and taste, but in this case, the basic recipe is practically identical everywhere, requiring only two ingredients: puff pastry (pasta de hojaldre), and sugar.

In English and French, respectively, the names “puff pastry” and “pâte feuilletée” define a very specific method of layering a flour-rich dough (détrempe) and a block of butter (beurrage); later, in the heat of the oven, the moisture in the butter produces steam and causes the pastry to puff. There is a more modern variation, in which the beurrage benefits from the addition of a small amount of flour, and it is rolled and used to wrap the détrempe, making it a reverse or “inside out” assembly method. Any other layered pastries have different names, but “puff pastry” is often (and wrongly) used as an umbrella term to describe any dough that becomes layered by using a generous amount of butter (or lard), so for example, phyllo (thin layers of dough brushed with melted butter and stacked, popular in Greece, Turkey, and other Middle Eastern countries), croissant dough (similar to puff pastry, but contains yeast) and even flaky dough (with fat mixed in), all get thrown in the same box as puff pastry.

In Spanish, the word “hojaldre” – “leafy”, actually may describe different doughs or pastries; pasta de hojaldre or pasta hojaldrada are the most common names to refer to puff pastry, and while phyllo is properly called pasta filo, croissant dough is the same as “hojaldre” or “hojaldra”, at least in Mexico, and flaky dough might be called hojaldre rápido (quick).

For my orejas, I decided to try making my puff pastry with the reverse method, used nowadays by many professional bakers, such as Anna Olson, who says that wrapping the beurrage (butter), over the détrempe (flour-rich dough) is “no more challenging a method than the traditional way, but it does result in a remarkably flaky and tender puff pastry that rises evenly and rolls out easily.” I also like the fact that the beurrage has some flour added to it, which probably also prevents the butter from spilling out of the layers while rolling, folding, or baking.

Puff Pastry (Reverse Method) –

Pasta de hojaldre (método invertido)

Printable recipe: Puff Pastry Reverse Method

Ingredients (for approximately 2 pounds)

Beurrage

1 ½ cups (338g) unsalted butter, at room temperature

½ cup (75g) all-purpose flour

Détrempe

2 cups (300g) all-purpose flour

1 tsp salt

1/3 cup (75g) unsalted butter

½ cup (120ml) water

More all-purpose flour, for sprinkling on working surface, as needed

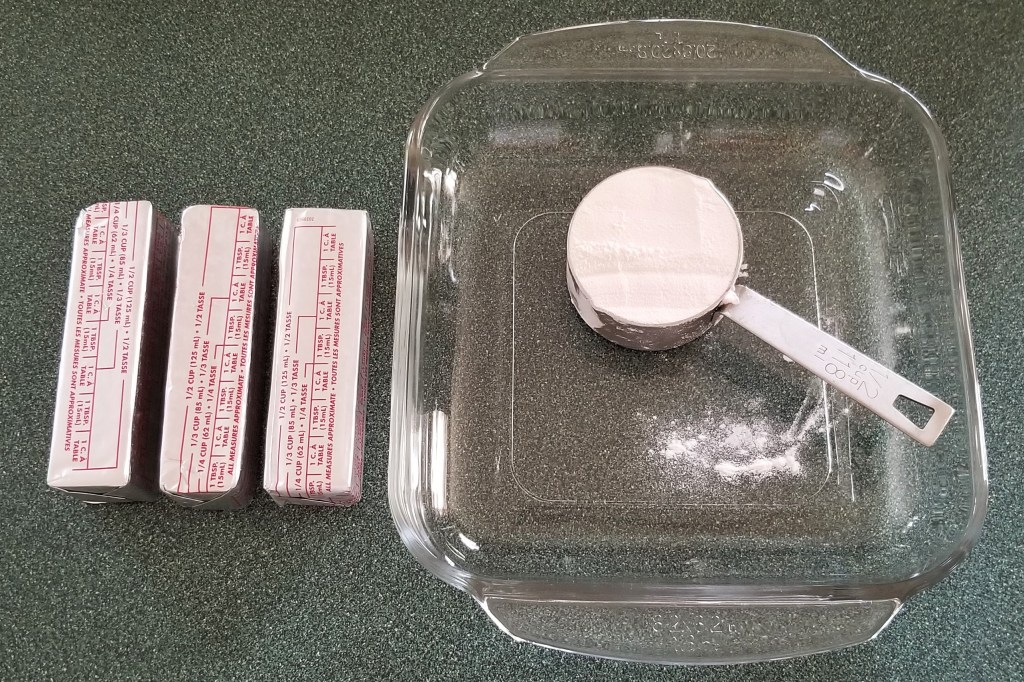

Prepare beurrage: Set up an 8x8inch (20x20cm) tray, flour, and butter:

Place flour in tray, then break up butter into the flour, using a pastry scraper or spatula (photo below, left); once all broken up, mix butter and flour with hands and/or spatula (photo below, centre), until a uniform paste is formed. Wrap in plastic (I used a freezer bag) and pat flat into the tray, to mould into a square (photo below, right):

Place tray in the fridge, and chill for about 45 minutes.

Prepare détrempe : Meanwhile, place flour, salt, and butter in a mixing bowl, then pour in water (photo below, left). Mix all together with hands and/or a spatula (photo below, right):

Continue kneading for a few minutes, until the mix becomes a manageable dough (photo below, left). Transfer to a floured surface, and using a rolling pin, form a 6x6inch (15x15cm) square (photo below, right):

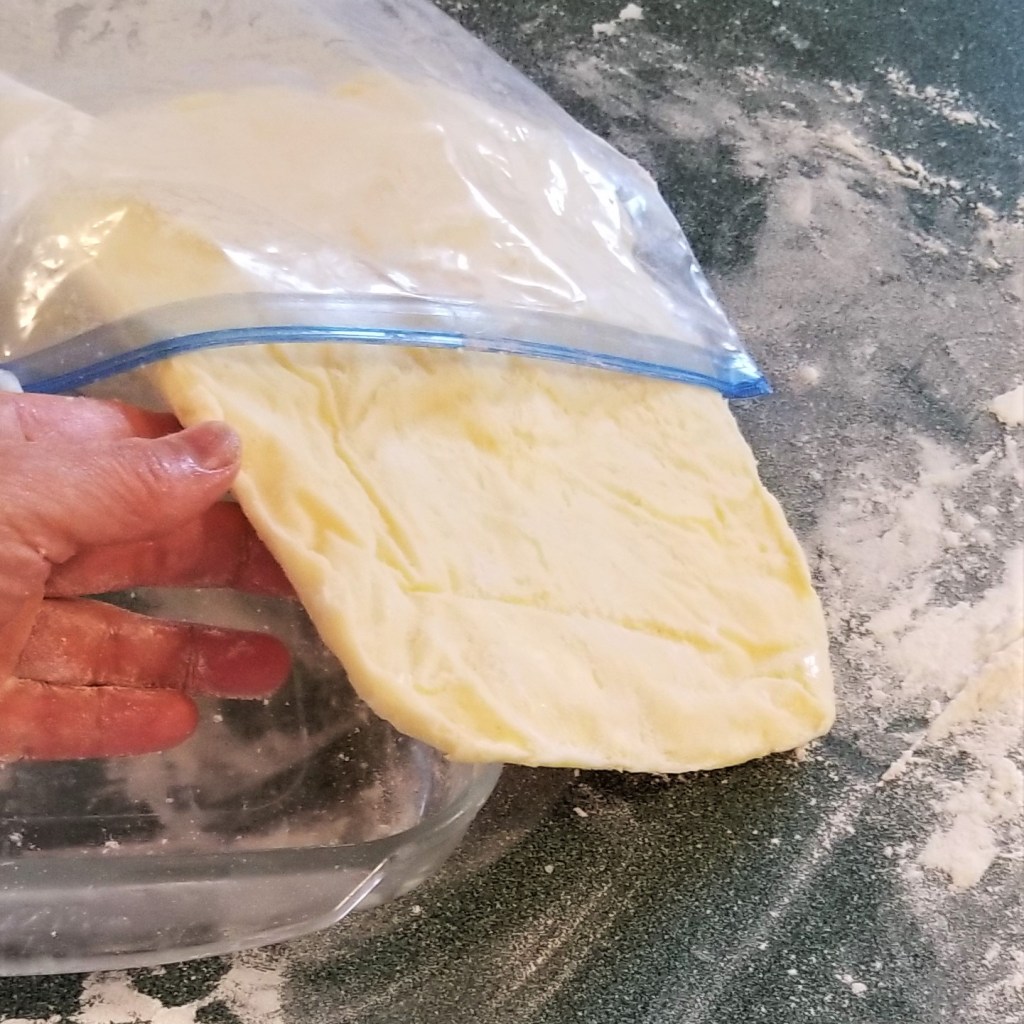

Assemble dough: After chilling time, unwrap beurrage and transfer to a floured surface (photo below, left). Extend into a sheet using a rolling pin, occasionally lifting from the surface with a scraper, and sprinkling more flour, as needed, to avoid sticking (photo below, right):

Continue rolling, to form a 12x8inch (30x20cm) rectangle (photo below, left); place détrempe in the centre of the rectangle (photo below, right):

Wrap berrauge around, to completely cover the détrempe (photo below, right). Sprinkle flour on top, and using the rolling pin, pound on the square to loosen up, and start thinning (photo below, right):

Roll assembled dough, sprinkling more flour, as needed, to avoid sticking to the pin or surface, to form a 15x9inch (38x23cm) rectangle, then brush flour off all the top, to avoid over-drying the dough (photo below, left). Fold over the top third of the length of the rectangle, then the bottom third over that (photo below, right):

This is the first fold, and the dough is a 5x9inch (12.5x23cm) rectangular trifold (photo below, left). Wrap in plastic (I used the same freezer bag, photo below, right):

Place wrapped dough in the fridge, to chill for about 45 minutes.

The pounding, rolling, brushing off, tri-folding, and chilling, will be repeated four more times, for a total of five folds, rotating the dough ninety degrees, each time, to always extend along the length of the rectangle, as seen in the photos below, for the pounding before rolling of the second fold (left), tri-folding of the rolled dough for the third fold (photo below, right) …

… brushing excess flour (photo below, left), and wrapping in plastic before chilling (photo below, right), both for the fourth fold :

After chilling the forth fold dough for 45 minutes, rotate and extend one last time (photo below, left). Notice how the dough has become firmer, smoother and more uniform at the edges with each progressive fold. Fold into thirds for the fifth time, and wrap again, to obtain around 2lb (908g) of dough (photo below, right):

The dough may be portioned, after chilling at least 45 minutes, before using, as seen below:

Any portions of dough may be kept wrapped, in the fridge for up to four days, or in the freezer for up to three months, thawing in the fridge the night before using.

Puff Pastry Palmier (Ears and Fans) –

Orejas y Abanicos hojaldrados

Printable recipe: Puff Pastry Palmier (Orejas & Abanicos)

Ingredients (for 14-16 pieces)

1 lb (454g) puff pastry (half my batch from above)

Granulated sugar, as needed

All-purpose flour, as needed

Orient the pastry block on a floured surface, so the folded edges are parallel to a rolling pin, and sprinkle flour on (photo below, left). Pound, then extend, with the rolling pin along that direction (photo below, right):

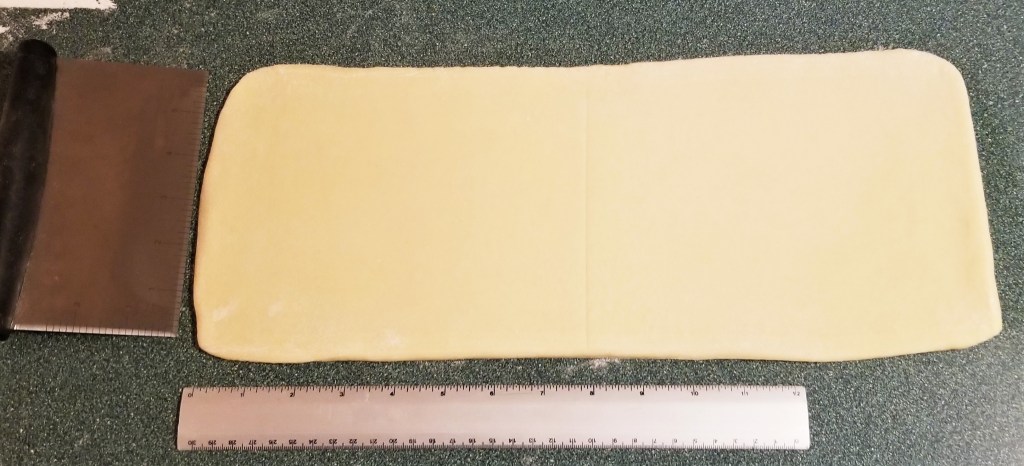

Continue rolling, to form a rectangle approximately 6x16inch (15x40cm), that is ¼ inch (6mm) thick, and mark with a line running perpendicular to the centre of the length:

Brush flour off the dough (photo below, left), then sprinkle all the top generously with granulated sugar (photo below, right):

Press sugar onto the dough with rolling pin (photo below, left); fold each edge over the sugared surface, to align with the centre line (photo below, right):

Pinch edges together (photo below, left). Press the seam down firmly with the handle of a wooden spoon (photo below, right):

Sprinkle with more sugar, then fold in half (photo below, left); sprinkle more sugar on outer sides, rolling with the pin (photo below, right):

NOTE: Some recipes call for sprinkling the outer surfaces with turbinado sugar, but I find it too grungy, and most Mexican recipes use granulated sugar exclusively.

Place folded block in plastic wrap (or bag) and chill in the fridge for half an hour to 45 minutes. Preheat oven to 400ºF (200ºC).

Transfer dough to working surface. Cut slices across the folds, approximately 3/8inch (1cm) thick:

Place the slices on their cut side on baking sheets lined with parchment paper, leaving about 2 inches (5cm) of separation, because they will puff mostly sideways:

To make the fan-like shape (abanicos), as shown on the right side at the top of this post, cut the loops open at the top of the slices:

Bake in pre-heated oven for 20 to 25 minutes, switching top and bottom trays, and turning front side of each tray to the back of the oven, to bake evenly:

Remove from oven when golden brown and puffed:

Allow to cool down for at least 20 minutes before eating. In the photo below, puffy and sweet oreja (ear) on the left, and abanico (fan) on the right:

The close-up below shows a crispy edge, and a multi-layered cross-section:

These crispy treats are so addictive, I have never had any leftovers long enough to try freezing, and anyway, they are at their best within a couple of days after baking, stored in an air-tight container on the counter, or in the fridge.

But who created puff pastry?

Puff pastry has been considered traditionally a French creation from the 17th century, with the first documented recipe published in François Pierre La Varenne’s “Le cuisinier françois” in 1651; the paragraph below is from a transcription of the University of Michigan of: “The French cook.: Prescribing the way of making ready of all sorts of meats, fish and flesh, with the proper sauces, either to procure appetite, or to advance the power of digestion. Also the preparation of all herbs and fruits, so as their naturall crudities are by art opposed; with the whole skil of pastry-work. Together with a treatise of conserves, both dry and liquid, a la mode de France. With an alphabeticall table explaining the hard words, and other usefull tables. / Written in French by Monsieur De La Varenne, clerk of the kitchin to the Lord Marquesse of Uxelles, and now Englished by I.D.G. La Varenne, François Pierre de, 1618-1678., I. D. G.

London: Printed for Charls Adams, and are to be sold at his shop, at the sign of the Talbot neere St. Dunstans Church in Fleetstreet, 1653.”

“THe puft paste is made thus. Take four pounds of flowre, allayed with salt and water, very sweet nevertheless; after it is a little rested, spread it with the quantity of two pounds of butter, joyn them together, and leave a third part of your paste empty, for to fold it up into three, and when your butter is shut up, spread your paste again very square, for to fold it up four-fold; after this, turn it up thus, other three turnes, and set it in a coole place, for to use it upon occasion. And then spread your paste proportionably to the pie or tourte which you have a mind to make up; and observe that this paste is harder to be fed than any other.”

There is currently some debate about puff pastry having an earlier Moorish/Spanish origin, as early as the 13th Century. For example, a recipe in “An Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook” (Andalusia, 13th c. – translated by Charles Perry) for “Preparation Of Musammana [buttered] Which Is Muwarraqa [leafy]” as posted in medievalcookery.com, describes a thinly rolled yeast-free dough that is brushed with clarified butter, rolled into a cylinder and patted, to form layers, then pan-fried and dressed with honey; Charles Perry and others avouch that this is a precursor of puff pastry. My opinion: It would certainly have layers from the rolling of the dough, but I fail to see how this recipe could be considered puff pastry, since clarified butter (in which much water has been removed) would not even produce enough steam to puff, and the confection is pan-fried, not baked. In the article “Puff Pastry Has a Rich History” (Sun Sentinel, 1998) the same writer, Charles Perry, argues that “…The 13th century cookbooks also mention a couple of ways of making layered pastry that start out with separate sheets of thinly rolled dough. One of them was called foliatil, which meant “leafy” in medieval Spanish (the modern Spanish word for puff pastry, hojaldre, comes from it). It was just thin sheets of dough, buttered, stacked up and baked.” My opinion: This sounds not like puff pastry, but actually like an exact description of phyllo.

There is also some argument about a couple of Spanish cookbooks, from the 17th Century, as is LaVarenne’s book, but pre-dating it; I got a hold of a PDF facsimile of one of them, “Libro del arte de cozina” (Book on the art of cooking) written by Domingo Hernández de Maceras, and published in 1607, in which the name “ojaldre” appears a dozen times, but the only paragraph resembling a recipe reads, in Old Spanish:

“para vn pastelon de quatro libras,

ha menester libra y media de harina y

vn quarteron de manteca de puerco,para hazer el ojaldrado, y ha menester

ocho marauedis de efpecias, y como tengo dicho para cada libra dos hueuos, y

caña de vaca, y fus yemas de hueu os”

My translation:

“for a large pastry of four pounds,

It is needed one and a half pounds of flour and

a quarteron [roughly 2.25 l] of lard to make the ojaldrado, and it needs

eight maravedis [and old type of currency in Spain] of spices, and as I have said, for each pound, two eggs, and

cow marrow, and its egg yolks”

My opinion: This recipe does not explain how to actually “make the ojaldrado”, and could well be referring to a simple flaky dough – “hojaldre rápido”, indeed a puff pastry, or even phyllo.

There is also a reference to “La vida del Buscón’ a novel by Francisco de Quevedo, written in 1604, and first published in 1626, with the word “hojaldres” appearing in Chapters IV and V, but Quevedo uses the word just to identify already made pastries, with no specific mention of the dough, or any method used. My opinion: Again, the word “hojaldre”, as explained before in this post, may define different types of pastry (flaky, yeasted), not necessarily puff pastry.

My conclusion: Although it seems to be a possibility that puff pastry might have evolved from Middle Eastern phyllo, the first documented, and fully described recipe of puff pastry, remains LaVarenne’s, and the French terms pâte feuilletée, beurrage, and détrempe are still widely used by modern day bakers and chefs; even if the method was probably developed organically over time, not as a serendipitous event, and it was not created by LaVarenne, he definitely deserves the credit for first documenting the full recipe, including the folding method, as we know it.

Of Revolution and Bread – Palmier made it to Mexico as orejas during the last years in office of Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz (rule 1884-1910), who favoured all things European; it is said that Díaz served orejas while entertaining his privileged friends, along with many other European sweets, and among lavish extravagances, while the tempo of life for the lower classes dictated heavy workloads, until the onset of the Mexican Revolution, on November 20, 1910. This put an end to Díaz’s rule in a matter of months, but the social injustices during those decades had caused so much resentment, that the rebellion then exploded into a cruel civil and guerrilla war that went on for many years. Social changes and industrialization over the following decades were slow, but eventually made pan dulce more affordable, and orejas in particular, quickly became a popular choice amongst Mexican families.

I am sharing my post at Thursday Favourite Things #516, with Bev @ Eclectic Red Barn, Pam @ An Artful Mom, Katherine @ Katherine’s Corner, Amber @ Follow the Yellow Brick Home, Theresa @ Shoestring Elegance and Linda @ Crafts a la Mode.

I am bringing my recipe to Full Plate Thursday #563 with Miz Helen @ Miz Helen’s Country Cottage.

I am joining Fiesta Friday #407 with Angie @ Fiesta Friday, this week co-hosting with Jhuls @ The Not So Creative Cook.

I am also sharing my recipe at What’s for Dinner? Sunday Link-Up #342 with Helen @ The Lazy Gastronome.

!Esta mui delicioso!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Heehee, Gracias!

LikeLiked by 1 person

De nada. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post and tutorial!

I used to make puff pastry from scratch, but over the years got spoiled and started buying it (only ones that are made with butter), which is very rare for me.

Your post made me feel like going back to making it. We’ll see… 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have you tried the reverse method? I really liked it, and I will not go back to the other way. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is excellent. I’ve also tried a few recipes for quick puff pastry (with the butter grated into the dough) with fairly good results.

But lately I’ve found a very good brand that uses butter, so I neglected making it myself. I’ll get back to it, as winter comes with staying more at home on cold days… 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! This was fascinating. I doubt I’ll ever be that ambitious a baker – store-bought dough for me. But I enjoyed learning how this is done, why the dough puffs and the history, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was very curious about the reverse method, but of course store bought dough is convenient and gives you orejas and abanicos in no time. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

I made puff pastry once. It requires a lot of time, but it was all worth it. These look perfect. Thank you for the tutorial and for sharing at Fiesta Friday party.

LikeLike

Thank you, Jhuls, and thank you for hosting!

LikeLike

They look amazing! And great instructions. I love inverted/reverse puff pastry too.😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your kind comment, Lili, it means a lot coming from a skilled baker such as yourself!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve never actually looked at a recipe for puff pastry before, thinking it will be very complicated. It is, but I realize now reading your post that I could do it. So thank you for that.

Interesting addendum on the history. Yes, it could be older, but documentation is also an important thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person