In one of my previous posts – about guacamole – I included a Science tidbit explaining why avocados turn brown after slicing or mashing. Because there are so many variables involved in this process during preparation of avocados in the kitchen, and there are so many different suggestions on how to prevent browning, I thought it would be interesting exploring browning of avocados, and trying to objectively identify ways to keep them green.

Just a little background:

Enzymes are molecules produced by living organisms; their function is to accelerate a chemical reaction taking place within cells. There is one enzyme specialized in accelerating each particular function, and each can be characterized by ranges of temperature and pH (acid/neutral/base) in which that enzyme will present optimum performance [1]. For example, pepsin is a digestive enzyme in our stomach; it is not surprising that pepsin’s optimum environment is: body temperature, around 37°C (98.5°F), and an acidic pH, between 1 and 4, the same as the gastric juice in our stomach [2]. Enzymes slow down at low temperatures, and recover when the temperature rises, but if over heated above a certain temperature , they will suffer permanent deformation, and become what is called denatured, ceasing to perform their function also permanently [3].

Enzymatic Browning is the process in which the enzyme polyphenol oxidase (PPO), present in fruits such as apples, bananas and avocados, facilitates the reaction of oxygen in the environment with polyphenols in the fruit, which ultimately causes browning. The optimum parameters for PPO are, again not surprisingly, temperatures between 15-35°C (60-95°F) the most common ambient temperatures where these fruits grow, and pH between 6.7 and 7, or neutral, like water; browning due to PPO will slow down for lower temperatures, and acidic or basic environments. The temperatures for denaturing PPO start at around 70°C (158°F), and quickly accelerate until at 100°C (212°F, water’s boiling temperature at sea level) PPO denatures almost immediately [4]. There are studies on apples that have found varieties with lower PPO activity (less browning) [5] and there are some genetically modified (GM) varieties commercially available. As of 2015, there were none for avocados [6].

With these facts in hand, I reviewed methods that people have tried to avoid or slow down browning in avocados:

Cover tightly – consistent with a physical barrier to avoid contact with oxygen in the environment.

Refrigerate – consistent with lowering temperature below the optimum temperature range for PPO activity.

Keep pit attached/in the bowl – Is it just a physical barrier or are there browning retardants in the pit?

Add lime/lemon juice – consistent with lowering pH below neutral, the peak for PPO activity.

Boil whole avocados for a few seconds – it is recommended to drop one avocado at a time in a pot of boiling water for exactly 10 seconds, followed by an ice bath [7]. It is consistent with permanently denaturing PPO at high temperatures.

Immersing in water, spraying with oil, adding chemicals – consistent with physical barriers and changing pH. I will not address these methods, because a prolonged water bath will affect texture, and oil and other chemicals will alter flavour. Presentation is important, but ultimately, the avocados and guacamole must be good to eat.

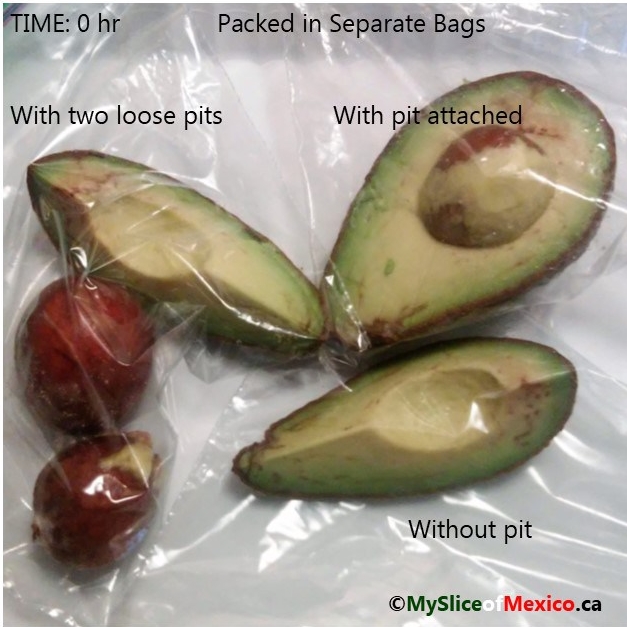

I think in general everybody has tried the first two methods with some degree of success. For the third one, I found several references in which people all agreed the method works only where the pit was blocking contact of the guacamole/avocado with air [8]. I tried an experiment to check if there was any other effect from the pits. I sliced one avocado in half, and placed the half with the pit attached in a sealed bag. I sliced the other half into two pieces, placed one piece in a separate sealed bag, and the last piece went in a third bag, along with two pits from other avocados. I left the bags on the counter for twelve hours:

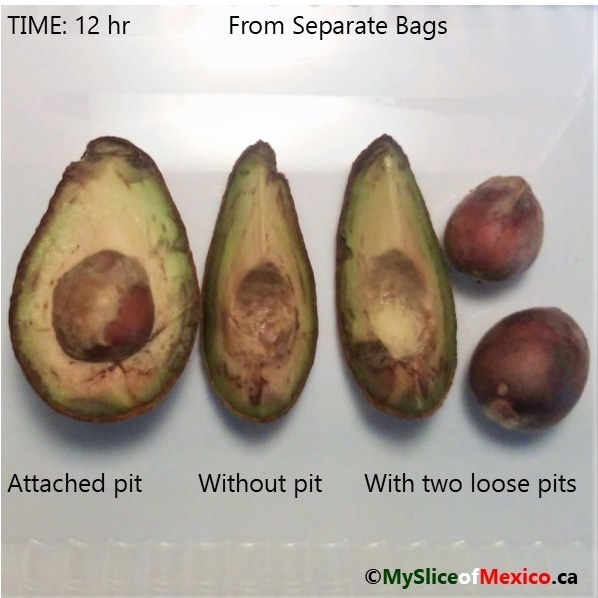

As much as I would like to say that the pieces with pits looked better than the one without – maybe the half with the attached pit looks a tiny bit better – there was really no significant difference. When I removed the attached pit, the flesh underneath did look better (ugh, you will have to take my word for that, I forgot to take a pic!)

While that was going on, I tried the other two methods left on my list: boiling for 10 seconds to permanently denature PPO, and the addition of citrus juice to create an acidic environment. I had four ripe avocados, bought together, kept at room temperature, and used at roughly the same time. There were two very close in size, a slightly bigger one, and the last was the largest (see photo below). I used the medium one for the pit experiment (above). For the other three, I assigned one of the small as my control sample (no heat treatment), and the other small and the large to be boiled; I wanted to see if size would be another characteristic to consider.

I set up a large pot filled with water, and while it heated up to boiling point, I got a slotted spoon and a stop watch, and prepared the acidic liquid. I did not want to spend a small fortune in limes or lemons, so I measured 12g of citric acid and 250ml of boiled water at room temperature; when mixed together, the acidic solution roughly corresponded to the citric acid concentration in lime juice [9].

I set up a large pot filled with water, and while it heated up to boiling point, I got a slotted spoon and a stop watch, and prepared the acidic liquid. I did not want to spend a small fortune in limes or lemons, so I measured 12g of citric acid and 250ml of boiled water at room temperature; when mixed together, the acidic solution roughly corresponded to the citric acid concentration in lime juice [9].

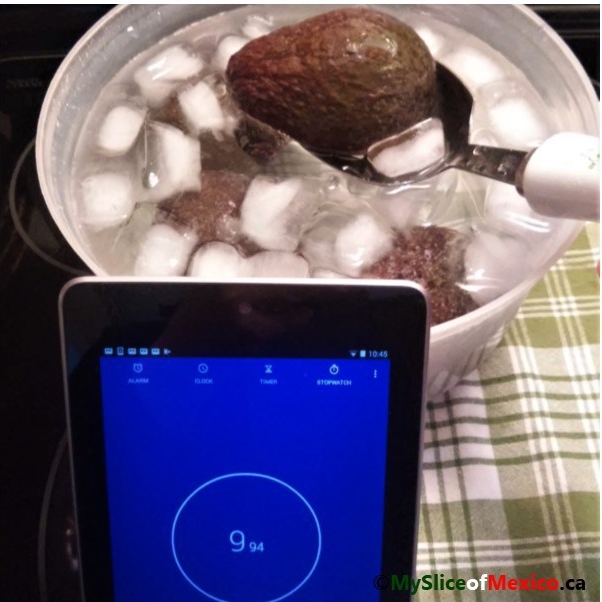

Before dropping the avocados in the boiling water, I set a large bowl with cold water and ice next to the stove. I boiled one avocado first, so I could fish it out of the water as close to 10 seconds as possible, dropped it in the ice bath, and I made sure the water was boiling before dropping the next avocado. I let the two avocados cool in the ice bath, then I patted them dry.

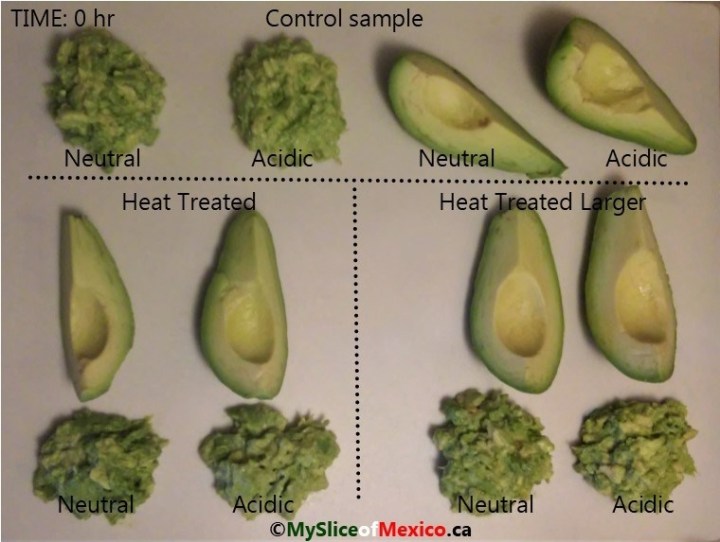

The two heat treated avocados and the control (not heat treated) were each sliced into quarters; 2 quarters were left in one piece, the other quarters were mashed. For each avocado, one piece was immersed in acidic liquid, and one mashed quarter was mixed with one teaspoon of acidic liquid. The other piece and mashed quarter had no contact with the acidic liquid (neutral pH). The photo below shows the control avocado at the top, the small/heat treated left, and the large/heat treated just after preparing it as described above:

This is how all the samples looked after slicing, mashing and mixing:

It was only me doing all the preparations, so I started with the large avocado, then the small/heat treated, and finished with the small/control. It took me around 3 minutes to prepare each, so technically, time 0hr corresponds to 9 minutes elapsed for the large avocado, and six and three minutes for the other two, respectively.

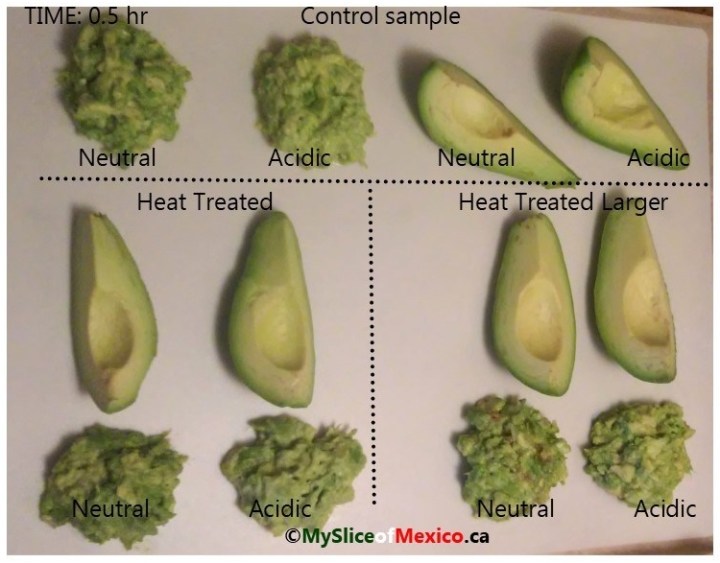

I came back to observe all the samples after half an hour:

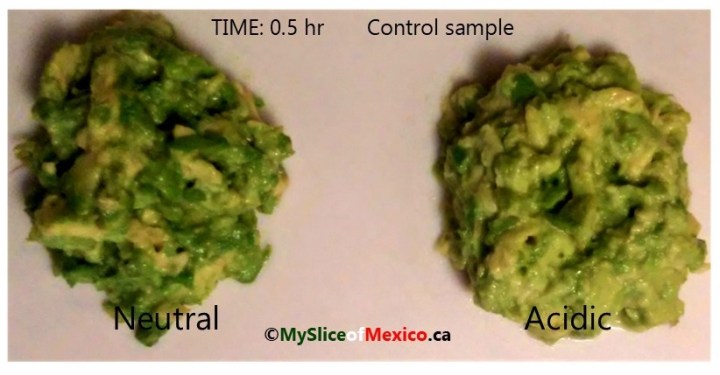

No change at all, but I noticed something with the mashed samples; the portion mixed with the acidic solution looked lighter than the neutral (not mixed). It was the same for all, in this photo, the control avocado as an example:

After one hour, the small avocados had not changed, but the large was starting to show some browning; as expected, the neutral mashed was the worse, but strangely enough, the one piece soaked in the acidic solution was turning a little as well:

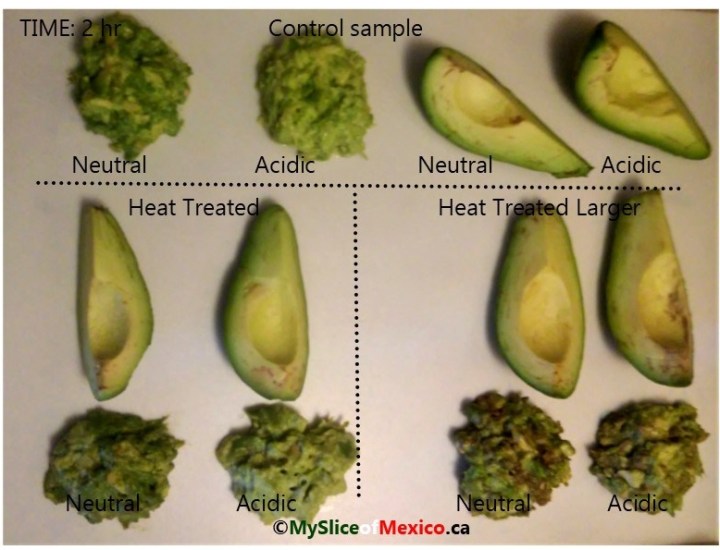

After two hours, a little surprisingly, the control sample seems to be doing the best, the small/heat treated changing like the large sample, neutral mashed and one piece acidic turning; the large is the worst:

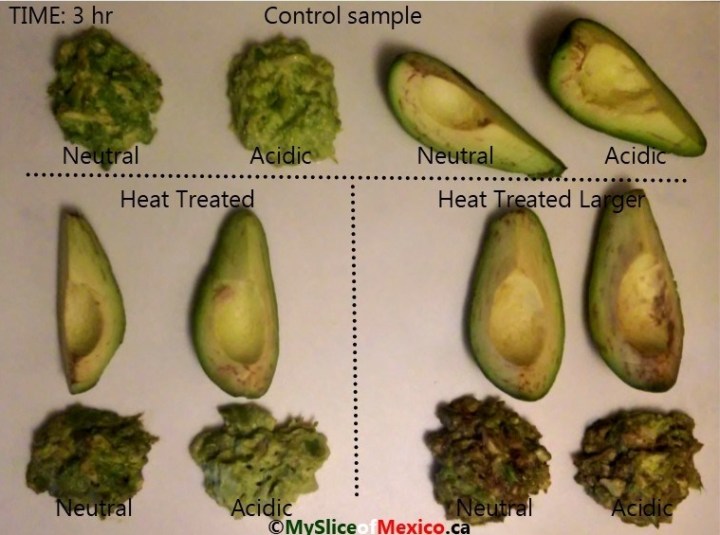

After three hours, the mashed neutral are the worst, along with all the samples from the large avocado; again puzzling for the large sample is that the acidic one piece is doing worse than the neutral:

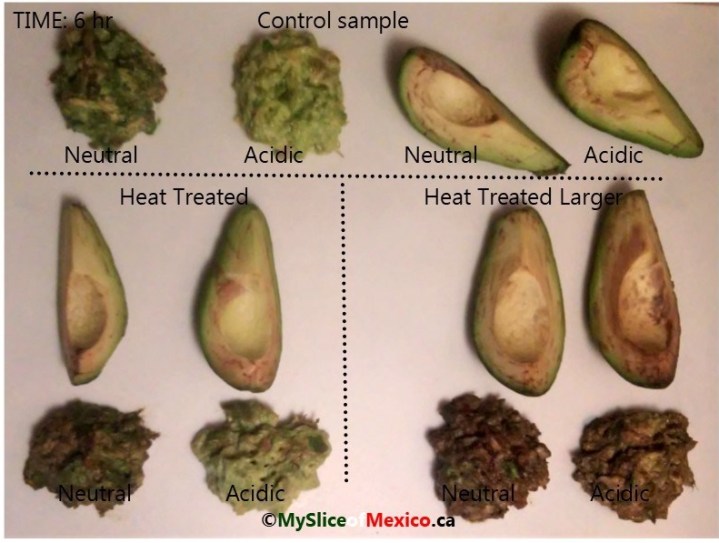

Finally, after six hours, there are some clear winners. All the samples from the large avocado/heat treated were the worst compared to the corresponding samples of the other two avocados; it seemed like the heat treatment made it worse when compared to the control/not heated avocado. When comparing the two small avocados, they seemed similar, although the mashed samples of the control/not heated avocado looked better. The best of all were the acidic mashed samples from the small avocados:

I did one last observation: at the end of the twelve hour pit experiment, I sliced a thin layer off from all the samples from that avocado (the medium one), and they were all green underneath:

Conclusions:

The heat treated avocados did not show slower browning when compared with a non heat treated control sample; in some cases, especially for mashed avocado, they were worse. This indicates that there was no control over how PPO did or did not denature during the heat treatment. Setting up a pot of boiling water and an ice bath is a lot of work, as well, which defeats the purpose of saving time by preparing the avocados in advance. I do not recommend this method.

The one piece samples did not seem to end very differently whether they were dunked in the acidic solution or not. This method worked the best for mashed avocado; the fact that it did not work for the mashed sample from the large avocado seems to indicate that one teaspoon of acidic solution was not enough for it, so when using this method in the kitchen, recipes would have to be adapted to increase the amount of lime juice for bigger avocados. Is this practical? My husband and I were brave Guinea pigs and tried the mashed acidic samples that looked good … they were very sour! I was even braver and tried the brown pile from the large avocado; it was ugly, but not very acidic.

The presence of avocado pits only changed the browning process when they worked as a physical barrier. What a pity! (LOL); the good news is that pit-less avocados are a reality [10], so it does not matter that they were not doing any good anyway.

For avocados in large pieces stored in sealed containers for twelve hours, slicing off the brown surface uncovered a fresh green layer.

In the kitchen:

Avocados in large pieces will keep presentable for about 6 hours. Covering or storing avocados in sealed containers will provide extra time, and brown surfaces can be sliced off last minute if there is any browning. I have noticed that many sushi bars keep their sliced avocado layered on plates covered with plastic, or inside containers with lids.

For mashed avocados, many recipes call for lime juice, so if the preparation needs to be stored, follow the recipe but set the lime juice aside. Place most of the prepared avocado in a container, reserving a couple of tablespoons in a bowl. Add all the reserved lime juice to the bowl, and mix thoroughly; carefully pour this – very acidic – mix on top of the preparation. Keep covered until serving time, when you can simply incorporate the acidic barrier to the bottom layer. The colour and, most importantly, the flavour, will not be compromised.

Note: A popular dish called “The Seven Layer Dip” takes all the toppings normally used for nachos, arranged in layers: refried beans, salsa, guacamole, green onions, jalapeño peppers, sour cream and grated cheese. I bet the guacamole stays nice and green buried in the middle of all the strata. If prepared in a clear bowl and served with corn chips, this dip is both beautiful and flavourful.

Hey, this seven layer dip is quite unique. I ll surely try this. Thanks

LikeLike

Wonderful! Let me know how you liked it

LikeLike