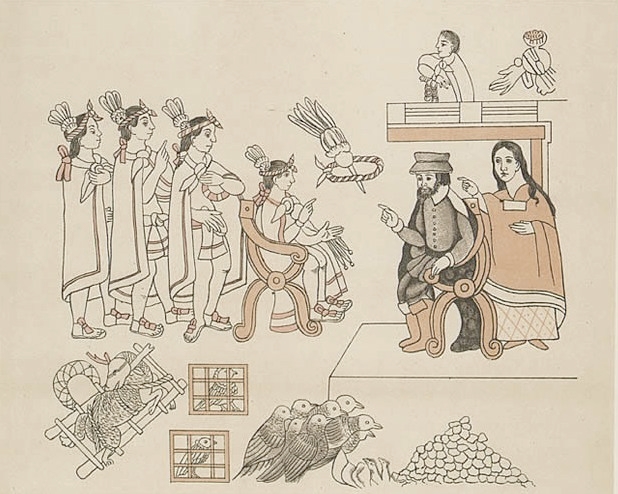

(Image: “Cortez & La Malinche meet Moctezuma II; Tenochtitlan, November 8, 1519″, from facsimile published ca. 1890 of the “Lienzo de Tlaxcala” ca. 1550 AD. Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons.)

“Wow, La Malinche must have had an interesting life. I wonder what happened to her …” Thank you to Cathie @ 2018 – A Year of Living Sustainably for her comment on a previous post, which gave the inspiration for this post!

To wrap up my Tabasco state theme, I am following up on the story of La Malinche, born Malinalli (in honour of the Nahuatl goddess of grass) and later called Malintzin (Lady Malin) by the natives and Doña Marina by the Spaniards. This is probably the first documented story of mestizaje (inter-mixing of foreign and indigenous people) in Mexico, told by Bernal Díaz del Castillo in his “True History of the Conquest of the New Spain” (“Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España”). I am translating and paraphrasing, in this shortened version of his recount:

“Doña Marina’s parents were Caciques (chiefs) of a town called Painala, which had other towns subject to it, about eight leagues from the town of Guazacualco. Her father died while she was still a child, and her mother married a young man, and bore him a son; Marina’s mother and step-father decided that the boy should succeed to their offices, and so that there would be no obstacle to this, they gave the little girl to some Indians [the Spaniards called the New World the West Indies, so these were Mexican natives] from Xicalango – at night so no one would see them – and told their people that she had died. Since a child of one of their slaves died, they announced that she had been their daughter (and no longer heiress.) The people of Xicalango gave the child to the people of Tabasco, and those gave her to Cortés. I myself met her mother, and the widow’s son (Marina’s half-brother), when he was already grown up and ruled the town jointly with his mother, for the second husband of the old lady was dead. When they became Christians, the widow was named Marta and the son Lázaro.

Cortés always took Marina with him. One time, much later, on the way to Honduras, he married Marina to a gentleman named Juan Jaramillo at the town of Orizava, before certain witnesses, one of whom was named Aranda, who lived in Tabasco, and this man told me about the marriage contract … And Doña Marina was a sapient person of the greatest importance, and was obeyed without question by the Indians throughout New Spain. I knew all this very well because it happened in the year 1523, after the conquest of Mexico and other provinces, and Cristóval de Olid revolted in Honduras, and Cortés was on his way there, and he passed through Guazacualco. When Cortés was there, he summoned all the caciques of that province to come before him in order to make a speech about our holy religion, and about their good treatment, and among the chiefs who assembled were the mother of Doña Marina and her half-brother, Lázaro. Some time before this Doña Marina had told me that she belonged to that province and that she was nobility there, the mistress of vassals, and Cortés also knew it well, as did Aguilar, the monk and other interpreter. It was in this way that the mother and the brother had come before Cortés, and her mother recognized clearly that Marina was her daughter, because she resembled her very much. And she and her son were afraid of Marina, believing that she had sent for them to kill them. When Doña Marina saw they were crying, she consoled them and told them to have no fear, that when they had given her over to the men from Xicalango, they did not know what they were doing, and she forgave them. And she gave them many jewels of gold, and clothes, and told them to return to their town, and said that God had been very gracious to her in freeing her from the worship of idols and making her a Christian, and letting her bear a son to her lord and master, Cortés, and in marrying her to such a gentleman as Juan Jaramillo, who was now her husband, that she would rather serve her husband and Cortés than anything else in the world, and would not exchange her place to be head of all the provinces in New Spain …

All this, which I have repeated here, I know for certain, and I swear to it … Doña Marina knew the language of Guazacualco, which is that common to Mexico [Nahuatl], and she knew the language of Tabasco [Chontal Mayan], as did Jerónimo de Aguilar, who spoke the language of Yucatán and Tabasco, which is one and the same [Mayan], so that these two could understand one another clearly, and Aguilar translated into Castilian [Spanish] for Cortés. This was the great beginning of our venturesome conquests and, thus, thanks be to God, things prospered for us. I have made a point of explaining this matter, because without the help of Doña Marina we could not have understood the language of New Spain and Mexico.”

Marina was the name that La Malinche was given after being baptized into Christianity; she eventually learned Spanish and became inseparable from Hernán Cortés as direct interpreter, mistress and mother of his son Martín Cortés (born in 1522), also known as “el mestizo”. Native groups saw them as a connected entity, and even called both her and Cortés Malintzin (the suffix -tzin may be used as Lady or Sir); their figures appeared next to each other in many codices (see image above), because he always spoke through her. After her marriage to Juan Jaramillo (by 1523, the conquest was completed, and Cortés’s wife was coming to Mexico from Cuba), it is known that she had a daughter, but then Marina disappears from the main historical scene, with just vague references dating her death between as early as 1529, and as late as around 1551.

Still a controversial figure in Mexico’s History, La Malinche has been the target of many negative references; often portrayed as a traitor to her people, the expression “ser malinchista” (“to be malinch-ist”) is applied to a Mexican who favours foreign traditions and philosophies over Mexican ones. Many historians, artists and feminists have revised Marina’s story with more benign eyes, as the symbol of mestizaje, acknowledging that her influence (on both sides) probably saved a lot of lives, and that she faced incredibly complicated situations, with very limited choice.

Wonderful blog today! What a story. Your book is going to be a best seller I am sure. What cookbooks ever give such great historical info? Love you. Anya

Irene posted: “(Image: “Cortez & La Malinche meet Moctezuma II; Tenochtitlan, November 8, 1519”, from facsimile published ca. 1890 of the “Lienzo de Tlaxcala” ca. 1550 AD. Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons.) “Wow, La Malinche must have had an interesting life. I “

LikeLike

Love you, too; thank you, dearest Anya!

LikeLike

It is so instructive to hear a woman’s plight from a male’s point of view. Of course she is grateful for having been given to men, bearing a child and given away in marriage after having been the prize of Cortez. Reading between the lines, what an amazing woman to go through such arduous trauma, basically being disowned, disenfranchised, sold into slavery, trained and schooled to accept a different culture and all its rules, a different religion, to be the perfect vessel for the Spaniard’s sperm. And to rise through all of it, learning their language, using her astounding talents and inherent feminine wisdom, determined to save her people through communication and connection, despite the personal tragedy she endured!

In other words, thanks for translating this. I love it!

LikeLike

Yeah, that “True History…” was also written from the conquerors’ point of view, to add to the list of biased circumstances; nevertheless, even in that case, Malintzin was respected, and it is still better to have a documented account over none. That is why I had to choose to simply translate, since she did not leave any first-hand versions of her story. Thank you for your comment, Victoria!

LikeLike

What a wonderfully complex story. A pity that it is not more widely known. I like your introduction to la tradicion Mexicana.

LikeLike

Thank you, I am glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike

Another great post, Irene.

LikeLike

Thank you, TUG!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had no idea! What wonderful history. Loved this!

LikeLike

Thank you so much!

LikeLike

I read your post with interest because several years ago, I read a novel about La Malinche in which the events were more or less as you’ve presented above, but from her point of view. I read it in Spanish, I think. I wish I could remember the name of it – it might just be named “La Malinche” – anyway, if you are interested, you could probably Google it and perhaps it’s available in English too. I had first heard of her through a song by a Mexican folk group called Los Folcloristas. It’s a ballad really because the lyrics are really a poem, ending with these lines: “Ay, maldición de Malinche/enfermedad del presente/¿cuándo dejarás mi tierra?/¿cuándo harás libre a mi gente?”

LikeLike

I hope the song is about the attitude of some Mexicans who prefer foreign policies and lifestyles over local, and not the person; I personally think of her as a smart woman who did her best to help under very difficult circumstances and few choices. I will look for the book, thanks for the tip and visiting my blog.

LikeLike